THE ECONOMIST: Will investing in Russia really bring America a $US12 trillion bonanza?

The Kremlin is making big promises to Donald Trump’s administration.

Over the past year, two parallel sets of talks have been held about ending the war in Ukraine. American-led negotiations with Russia have produced proposal after proposal but no agreement on territory or security guarantees.

Meanwhile, other envoys from the Kremlin and the White House have been discussing business. Volodymyr Zelenskyy, citing Ukrainian intelligence, says Russia has promised deals worth $US12 trillion ($17t) to America in return for sanctions relief; one insider reckons a package has already been agreed on.

In Europe fears are rising that President Donald Trump could force Ukraine into crippling concessions by June — his latest deadline for peace — to chase gold in Russia.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Promises of enrichment have long lain at the heart of Vladimir Putin’s strategy. Before the Russian president met Mr Trump in August, The Economist understands, a note was drafted for Russia’s National Security Council explaining how to sell “the Greatest Deal” to Mr Trump.

Since last April Kirill Dmitriev, who runs a Russian state fund, has met Steve Witkoff, Mr Trump’s special envoy, at least nine times. Individuals close to the Trump family have been in talks to acquire stakes in Russian energy assets. America has been offered deals for Arctic oil and gas, rare-earth mines, a nuclear-powered data centre and a tunnel under the Bering Strait. Both sides stand to benefit. Russia is suffering from low oil prices and stricter sanctions. America’s president wants results before the November midterm elections.

The idea of America winning a $US12t prize — equivalent to six times Russia’s annual economic output — is plainly hyperbole designed to please Mr Trump. What might the real reward for peacemaking be?

To distinguish the treasure from the trap, we spoke to dozens of former officials, intelligence professionals, energy executives and corporate confidants. Optimists argue that Russia’s cheap energy, vital minerals and 145 million consumers could be a huge boon to Western firms.

Our analysis, however, suggests that the available riches are a small fraction of what the Kremlin is touting. Worse, China is already beating America to those prizes that are on offer.

Steppe change

Sanctions might appear to have curbed Western firms’ enthusiasm for Russia, but look closely and plenty are still interested. Insiders say Western oil majors met with their former Russian partners during ADIPEC, an energy conference in Abu Dhabi in November.

Many American lawyers worked overtime last summer, after Mr Trump pressed Ukraine into a new set of negotiations, to study possible scenarios in which sanctions were lifted, says Patrick Lord of Risk Advisory, a consultancy. Much preparatory work, in other words, is already done.

The Russian branch of the American Chamber of Commerce still holds regular events, on topics ranging from food and consumer goods to taxes and human resources.

At least five American firms that had left Russia, including Apple and McDonald’s, have recently registered new Russian trademarks.

The Economist understands that, when Mr Putin met Mr Trump last year, he offered to return $US5 billion-worth of assets that Russia seized from Exxon Mobil, an oil major, in 2022. “Kirill Dmitriev has been largely successful in his efforts to whet the appetite of the American business community,” says Charles Hecker of RUSI, a think-tank in London.

Before 2022, the Western firms that did business in Russia were largely European rather than American. Now, America hopes that by bringing Russia in from the cold its companies can reap the benefits. Three prizes might be on offer: a boom in trade, access to stranded assets and the chance to extract natural resources.

Start with trade. In 2021, when the European Union still traded with Russia, its sales of goods there came to €90b billion ($151b). Those included €40b-worth of machinery and transport equipment, much of it to serve Russia’s mining, oil and gas industries. Other big categories were chemicals (€20b) and manufactured goods (€9b), such as consumer appliances and scientific kit. Russia’s goods imports from America, by contrast, were just $US6b — though if Mr Trump and Mr Putin now strike a peace deal, American firms might well grab a bigger share of Russia’s business.

Commodity traders could also win from a reopening. Russian exports of energy, food and metals are now being handled by obscure brokers, “shadow” tankers and state-backed insurers that evade sanctions. But that system is expensive to run and Russia would relish the financing Western merchants can offer. Once sanctions fall, they might be invited to skim logistics fees, financing charges and trading profits from these sales, which amount to some $US300b annually.

“Russia is the world’s biggest wheat exporter,” says an American trader. “We would like to be involved.”

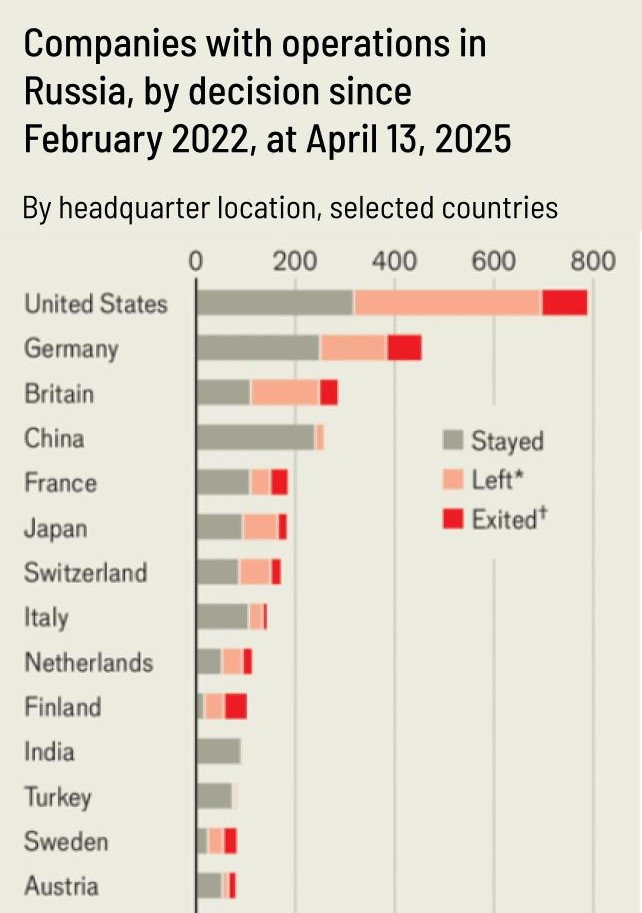

Another prize may await American firms that operated in Russia before the war—and those that can capture niches once occupied by Europeans. Some never left. The Kiev School of Economics (KSE) estimates that 324 American companies, ranging from Allied Mineral Products, which makes ceramics, to Zoetis, a drugmaker for animals, remain up and running in Russia. Their combined profits, however, are small, stretching to only a few billion dollars in 2023. This capital has nevertheless been accumulating in Russian accounts, and might be repatriated if capital controls and sanctions were lifted.

Meanwhile, Western firms that left might return. The KSE counts more than 1500 of them, with many in finance, electronics and consumer goods. Plenty sold their Russian assets at steep discounts to local partners; some sales contracts gave Western firms the option to repurchase assets after the war. In discussions with America, Russian officials have suggested that firms without such contracts may nevertheless be given the chance to buy them back. Those assets, though, have last been valued at a total of $US60b.

Moreover, American companies can hope to sell only so much to Russians. Their $US2.2t economy is smaller than Italy’s, with a shrinking middle class. The KSE estimates that, in 2021, the total annual profits made by the 1500 foreign firms operating in Russia that it tracks were just $US18b, from revenues of around $US300b.

What most excites Mr Trump’s envoys, therefore, are potential stakes in mega-projects that could transform the world’s commodity markets. Russia’s National Security Council document describes its “treasure trove of Arctic and northern resources” that “a dozen sovereign and private funds from the USA and other currently hostile countries” would rush to exploit. “Everyone”, it adds, “will earn a lot of money.” Naturally, “Presidents Putin and Trump could potentially receive Nobel Prizes.”

The prizes on offer could indeed be large. Most of Russia’s oilfields are old and significantly depleted; to keep production flowing, the country needs vast injections of foreign technology, workers and capital. This might foster a shale revolution in West Siberia, which may have 12 billion barrels of recoverable oil and gas, estimates Artem Abramov of Rystad Energy, a consultancy. That is about 7 years’ worth of crude production from the Permian, America’s main shale basin.

Arctic Russia has even more untapped potential. With enough investment and an oil price near $100 a barrel, reckons Rystad, the region might yield nearly 50 billion exploitable barrels, starting in the 2030s. Central to this ambition is Vostok Oil, a project run by Rosneft, Russia’s largest energy firm, which requires 15 new towns, three airports and 3500km of power lines, at a projected cost of $US160b. The venture has been delayed by sanctions but Rosneft claims it could produce up to two million oil barrels per day by the 2030s — equivalent to 2 per cent of the world’s current production.

What is more, Russia’s far north is thought to harbour 29 million tonnes of rare earths, equivalent to 74 years of global output. To exploit them, the country is developing the Angara-Yenisei Valley, a $US9b Siberian processing hub overseen by Sergei Shoigu, who runs Russia’s Security Council. Russia hopes that a special economic zone, new infrastructure links and tax breaks will lift its share of global rare-earth mining from 1.3 per cent today to 10 per cent by 2030. This might include “heavy” rare earths, which are the scarcest and most valuable.

Moscow rules

A White House eager to end the war in Ukraine and enrich Americans could hardly fail to see the attractions of this prospectus. But how big would the peace dividend actually be?

Releasing the Russian economy from sanctions is easier said than done. Western countries have imposed nearly 23,000 penalties on it in recent years. Mr Trump’s pen can strike out some. But lifting many others, including on most banks and energy projects, would entail consulting a Congress that includes many Russia hawks. Spooks and diplomats think that Europe will be very reluctant to lift its own sanctions. And history suggests that lingering uncertainty would put off multinationals. Very few returned to Iran after key sanctions on it were suspended in 2016, despite prodding from European governments.

Perhaps Mr Trump would succeed in convincing others to give Russia a chance. But he has little control over how it runs its own affairs. Even pre-war, foreign firms in Russia were often one wrong move away from politically motivated punishment. The situation is even dicier now, says John Kennedy, a former British trade envoy currently at RAND Europe, a think-tank. The taxman is rapacious; the courts are corrupt; contracts are worthless. The Economist understands that the Russian firm that bought the local franchise of McDonald’s, which retained an option to repurchase, will demand extra money before considering the request.

Moreover, a peace deal that leaves Ukraine demoralised and defenceless would encourage Mr Putin to invade again — which would mean sanctions snapping back. Capital controls would return and the military-industrial complex would crowd out other sectors. Western firms would be back to square one, or worse.

Another complication is that many niches Westerners abandoned in 2022 have since been occupied by firms from Asia, Turkey and elsewhere. China supplied 57 per cent of Russia’s goods imports in 2024, up from 23 per cent pre-war. The highway linking Moscow’s main airport to the city, once bordered by European and Japanese car dealers, is now lined with Chinese ones. Russia’s “unlimited friendship” with China, which is as unequal as it is unlimited, has seen 30 per cent of Russia’s trade denominated in yuan.

Russia is also flooded with “parallel” imports of Western goods, illegally resold from the Gulf or China, that would undercut new sellers. iPhones cost less in Moscow than in London, notes Nabi Abdullaev of Control Risks, a consultancy. As inflation and unemployment surged after the war, the Kremlin would have little incentive to discourage black markets.

In science and technology the Russian government is calling for more autonomy, not openness. Native lawyers, accountants and admen — often graduates of American or British universities — have replaced Westerners, says Thane Gustafson of Georgetown University. Even in resource extraction, state giants may prove reluctant to share shrinking spoils. An oil “superglut” this year and next may depress the global crude price to near $US55 a barrel, a third of its level when joint ventures between Russian and Western firms peaked in the early 2010s. Another glut, of liquid natural gas, will also cut exporters’ profits.

Those mega-projects for which Russia needs Western help are fraught with difficulty. Most surveys of the Arctic’s mineral wealth date back to Soviet times; how much can be profitably extracted is unknown.

“To an extent, all we have is Rosneft’s word,” says John Gawthrop of Argus Media, a price-reporting agency. Building roads, railways and ports is costly and precarious, especially in the far north. Shipping oil from Vostok would require some 50 ice-class tankers, yet it has only one, notes Craig Kennedy of Harvard University.

Some oil blocks included in the projects overlap with licences held by other Russian firms or state agencies, creating thickets of legal and political risks. Before BP, a British oil major, sold its stake in a local joint venture to Rosneft in 2013, it spent years wrangling with its Russian partners.

Could Exxon Mobil, which sealed tie-ups with Rosneft in the early 2010s to invest $US500b in Russia’s Arctic, Black Sea and shale basins, be open to talking to its former partner again? (Exxon wound down its Russian operations after 2014, when Russia’s seizure of Crimea triggered Western sanctions.) If so, it is unlikely to bet too much.

The risks of committing huge sums to Russia for decades — when no one knows if a ceasefire might last a month — have ballooned. And the rewards are smaller, at a time when big offshore drilling opportunities exist elsewhere.

Russia’s rare-earth dream faces the same practical difficulties as other Arctic ventures, plus one more. China, which has a near-monopoly on rare-earth mining and processing worldwide, keeps a tight grip on the know-how required to extract and refine such ores. It has so far proved reluctant to share it with Russia, lest it become a rival or leak secrets.

Champagne on ice

All this suggests that, for as long as Mr Putin is in power, there is little potential for a new El Dorado in Russia. Suppose Russian imports returned to the levels of 2021, with America supplying an improbable 50 per cent of that (or $US190b a year). Then suppose the total revenues of all foreign firms in Russia recovered similarly, and American ones grabbed half of that, too ($US150b).

The two would still only amount to annual flows (not profits) of $US340b a year. It is extraordinarily unlikely that even these flows could last, uninterrupted, for the decades they would take to amount to anything near the Kremlin’s “$12 trillion” promise. That American firms might extract trillions of dollars’ worth of resources from the Russian Arctic similarly looks wildly unlikely.

Individuals close to the White House might nevertheless secure lucrative deals for themselves. One Washington insider says some have talked with Kremlin envoys about board seats at Russian companies.

New property developments, and the rents from utility assets such as pipelines, could line a few more pockets. Mr Dmitriev has form in such attempts to sway American officials. A report on Russian espionage, prepared in 2020 by the American Senate’s intelligence committee, counts 152 references to him, mostly concerning efforts to co-opt people close to Mr Trump.

Should the White House take the bait, the rest of America will wait in vain for a windfall as political costs mount. Congressional hawks would loathe it if a reopened Russia started rewarding its allies, particularly China.

More trade, finance and investment would soon allow Russia’s economy to recover, paving the way for the next war. Any president with America’s interests at heart would look at Mr Putin’s “$12 trillion” offer with a gimlet eye — and walk away.

Originally published as Will investing in Russia really bring America a $12trn bonanza?