THE ECONOMIST: Xi Jinping’s anti-America summit as a line-up of USA sceptic world leaders gathers in Tianjin

THE ECONOMIST: China’s summit of world leaders highlights growing global discontent with American dominance.

You may think the place where national leaders gather to talk about the future of the world is Washington DC, or perhaps the UN Headquarters in New York. In fact, as President Xi Jinping plays host to over 20 presidents and prime ministers in China, a new reality is taking hold. —

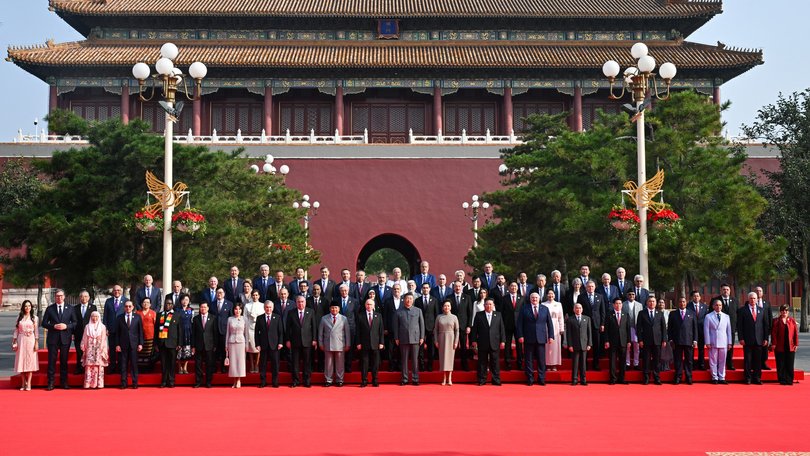

The formal rationale for getting together is a summit of the Shanghai Co-operation Organisation (SCO) in Tianjin, followed by the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the end of the second world war, including a military parade in Tiananmen Square.

For Mr Xi the gathering has a higher significance. It shows, he says, that China has become a global leader and the source of stability and prosperity. The origin of uncertainty today is America, he argues, which is unleashing trade wars with almost everyone, and undermining its own network of military alliances and security partnerships.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Mr Xi’s guest list is impressive. It is one of the largest get-togethers of autocratic regimes in living memory, with Vladimir Putin of Russia, Masoud Pezeshkian of Iran and Alexander Lukashenko of Belarus in attendance. Kim Jong Un of North Korea travelled by armoured train, in his first visit to China since 2019.

Even more striking is the presence of leaders of countries that have in recent decades leaned more to the West, including Turkey, Egypt and Vietnam.

Most striking is Narendra Modi, signalling India’s shift from America towards China. That follows Donald Trump’s disastrous double-fault singling India out for sky-high tariffs and embracing its enemy, Pakistan, following a conflict in May.

Mr Xi’s claim to lead a global coalition of America-sceptic powers is not as fantastical as you might think. Regarding trade, where all countries want predictability, China’s boast to be an anchor of stability now rings true — at least in relative terms. The country is already the largest goods-trading partner of most of this week’s visitors, along with another 100-odd states around the world.

As the Trump administration pursues a rolling campaign of economic warfare against its trading partners, China’s sins of mercantilism and state-capitalism look minor by comparison.

There is also a new-found unity opposing sanctions, including the extraterritorial threat America uses to sever individuals, firms and countries from the dollar-based financial system and tech platforms. Once these were mostly feared by pariahs and rogue states. Mr Trump wields them with ever less restraint and without a predictable legal process or institutional framework. Russia, and increasingly China, are already moving away from dollar payments.

Building a trusted, efficient alternative international system is daunting, perhaps impossible, especially for regimes without the rule of law. But more and more countries are interested in exploring options other than America’s dollar system. Even Europe is promoting a global euro. And fewer countries will be interested in enforcing American sanctions on its behalf.

In military affairs, the unity is less impressive. Only a smaller subset of countries, mainly autocratic ones, will attend the parade in Tiananmen Square in Beijing. India will not be there and opposes China’s military buildup after skirmishes on their Himalayan border.

If the autocrats spend long enough at the parade, they will find plenty to squabble over. Those neighbouring China will watch the PLA’s latest missiles and other weaponry trundle past them with distinctly mixed feelings. Yet security co-operation between autocracies is deepening. Russia and North Korea are working on space and satellite systems. In return for China’s support over Ukraine, Russia is thought to be offering it ever more of its most sensitive military technology, including submarine propulsion and missile-defence systems.

The weakest part of Mr Xi’s campaign concerns international institutions and rules. He has just declared that global governance has reached a new crossroads. State media propose that China works with like-minded countries to resolutely safeguard the purposes and principles of the UN Charter, and build a more just and equitable global governance system.

Although they are cloaked in the language of multilateralism, these are code words for a China-friendly world order in which big powers, including the People’s Republic, dominate spheres of influence and thereby enjoy more rights than small ones. Few countries in Asia want a region that is run by China.

Not everyone at Mr Xi’s big bash agrees with each other on everything. The SCO is a far cry from a NATO-style alliance. Other than the unifying factor of opposition or unease with Mr Trump’s America, these countries often have little in common.

Yet convening disparate parties with different interests is not a sign of weakness. It is what superpowers are uniquely able to do. The spectacle of China shepherding much of the world through Tianjin and Beijing was unimaginable even five years ago. Mr Xi’s guest list does not demonstrate that China yet runs a new world order. But it does show how much damage Mr Trump is doing to American interests.

Originally published as Xi Jinping’s anti-American party