Cancelled culture: Why our TV favourites get the axe

And Just Like That is almost over, and we probably should’ve seen it coming. But ratings and viewership aren’t the only reasons some shows don’t make it in the long run.

The beauty of TV is its longevity.

When done well, TV is a character-driven medium where the plot machinations often play second fiddle to just hanging out with the characters.

Obviously, this works better for certain genres, such as comedy, while others such as spy thrillers have schemes and capers as their story engine, but the best of them, such as Slow Horses, can balance both.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.As audiences, we approach TV and film differently. With TV, we’re ready to settle in, to plunge into the world, and to welcome these characters into our homes. We want to emotionally invest.

There were seven seasons of New Girl but almost nothing really happened during that run. What you remember is character growth, and the wild antics of the gang playing True American.

This isn’t meant to sound pathetic, like we’re all Nigel Nofriends who have to be mates with fake people living inside a box. But we do form something resembling a parasocial relationship with fictional characters when we check in on them with perhaps more frequency than we do our real-life amigos.

But TV is also an entertainment business, hinged on whether the economics are still there for a series to keep going. Rare is the title whose continued existence relies on art or creativity.

Shows are cancelled often capriciously and sometimes without notice. Given that, it can be difficult to decide whether or not this is the show or these are the characters you’re going to invest in, unless you know they’re going to stick around.

Sure, there are miniseries or anthologies. You know you shouldn’t get too attached to anyone from The White Lotus because even if they survive the season, they’re not coming back. But you’re prepared for that.

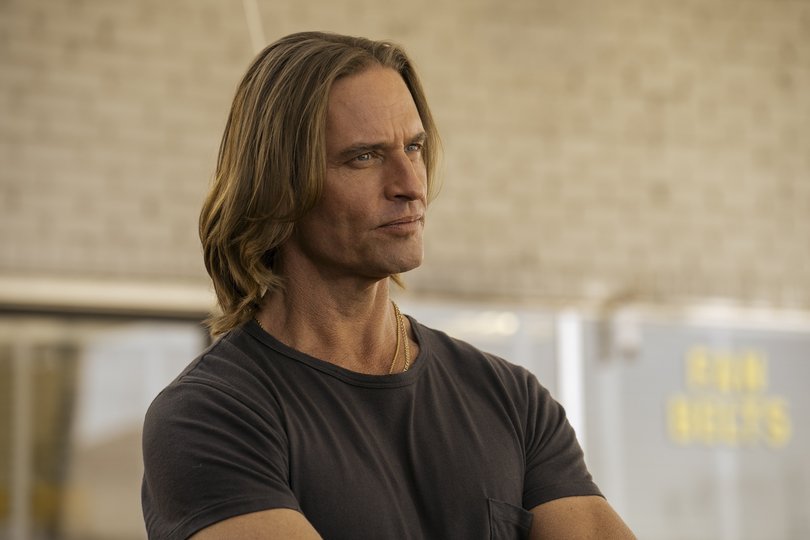

House of Cards is often considered Netflix’s first original series but Lilyhammer, a crime drama-comedy starring Steve Van Zandt, which the streamer co-produced with Norwegian broadcaster NRK1, preceded it by a year.

Lilyhammer dropped on Netflix in February 2012 and the streamer didn’t cancel a single original series until September 2014 when it said Hemlock Grove had been renewed for a third and final chapter.

Even though TV series have been axed since the start of the medium, Hemlock Grove’s cancellation was actually kind of shocking. For two and a half years, Netflix kept commissioning and renewing shows, and it seemed like the culls of broadcast were going to be different with streaming.

A decade on and it is different, even, in some ways, crueller. Because audiences and fans don’t see it coming.

Broadcast ratings are largely transparent, and you have some idea whether an ongoing show is doing well. While we were all processing the news this weekend that And Just Like That wasn’t coming back, one titbit we missed at the start of season three was that the opener ratings was down 62 per cent on season one, according to third-party stats from Samba.

We should’ve seen it coming – and probably many did.

In the past, fan communities have rallied when their shows looked on the verge of cancellation – Trekkies staged protests and a letter-writing onslaught in 1967 and bought goodwill for another season, while strong DVD sales of Family Guy and Arrested Development revived already axed favourites.

Now, the tea leaves are much harder to read.

Streamers are notoriously opaque when it comes to how many people watched something. Netflix is the only one who consistently releases numbers, and it took a long time for it to come to the table.

The others including Prime Video, Disney, Paramount and Apple sometimes crow about a success with vague statements about percentage growth or that it was the most watched title on its platform in X number of markets, but there’s no concrete context around any of that, so it may as well be nothing at all.

In the US, measurement company Nielsen collates streaming data through its own platforms but it doesn’t do that for Australia.

There’s also the fact that how many people watched it is just one factor into whether a series is renewed.

A lot of hands have been wrung over the cancellation of Australian Netflix series Territory, an outback cattle ranch drama that drew on the traditions of Dallas and Yellowstone. It seemed to be doing well, it hit the top 10 in many countries when it was released and was 39th most watched on Netflix globally in the second half of 2024, attracting 19.5 million views.

But it didn’t get a second season, which was the subject of some confusion locally. Territory was not a cheap show to make, shot almost entirely on location in rural Northern Territory, which is a massive logistical challenge in terms of bringing in crew and setting everything up, and that’s before you factor in the repressive heat which makes filming near-impossible for most of the year.

In the matrix of effort and cost versus reward, Territory didn’t score high enough.

The same could be said for The Residence, Netflix’s White House murder mystery starring the brilliant Uzo Aduba. It was the 23rd most watched series for the six months to June and drew in 33 million viewers, but it was also an expensive production with elaborate sets and a huge ensemble cast. Someone crunched the numbers and said, not worth it.

The Recruit was canned after its second season despite ranking 34th with 24 million viewers, because at least on paper, it didn’t compare favourably to the similarly themed The Night Agent (9th and 53 million), which had been released within a week of each other.

Other high-profile cancellations recently have included the Jeff Goldblum-led comedy Kaos, the Armando Iannucci showbiz satire The Franchise, the Frasier revival, J.J. Abrams 1970s crime caper Duster, Chuck Lorre sitcom Bookie, crime soapie Grosse Pointe Garden Society, the LA spin-off of Suits, and a TV reboot of Cruel Intentions.

Ratings are no longer the be-all and end-all of whether a show gets to live and fight another day – although they certainly were a huge factor in the end of The Project and Q&A.

Or sometimes it’s not the “right” kind of people watching, for example, when A Place to Call Home was canned in 2014 despite averaging a million viewers but too many of them were in the over-55s demographics that prime-time advertisers weren’t interested in. The series later ran for another four seasons on Foxtel.

The Late Show with Stephen Colbert was the most watched late night show in the US but got the axe because of it was, allegedly, losing tens of millions a year, and was caught up in the grist of a corporate merger being held up by the Donald Trump-controlled Federal Communications Commission.

There were also the two spin-offs in the Citadel would-be franchise, which Prime Video was trying to build as a big blockbuster streaming universe with Avengers filmmakers Anthony and Joe Russo. It was an enormously expensive enterprise with a production budget for the first season rumoured around the $US300 million mark, and then failed to make a dent in the zeitgeist.

The two spin-offs, Diana and Honey Bunny, came out last year while the second season of the main series was still in production.

That wasn’t the only reason the whole Citadel misadventure was being wrapped up – it was also the idea of its former studios boss Jen Salke, who was “exited” out of her role earlier this year. It would be very surprising if Citadel gets a third instalment.

Association with a particular person can be a boon but it can also be a show’s downfall.

Popular sci-fi series The Sandman wrapped after its second season after its creator Neil Gaiman got taken down by allegations of sex assault and abuse. Similarly, Gaiman’s series Good Omens had its third season turned into a single 90-minute episode in the aftermath of the controversy.

It’s a hard time to be a fan. You have to be prepared to have your heart broken.