THE NEW YORK TIMES: Why Donald Trump won’t say he wants Ukraine to win

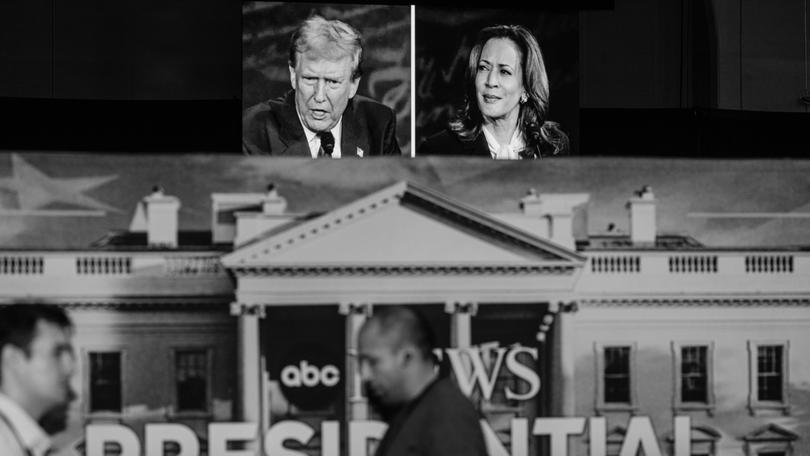

DAVID FRENCH: It’s understandable that many millions of Americans have focused on Springfield, Ohio, after the debate between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris. But it wasn’t Trump’s only terrible debate moment.

It’s certainly understandable that many millions of Americans have focused on Springfield, Ohio, after the debate between Donald Trump and Kamala Harris.

When Trump repeated the ridiculous rumour that Haitian immigrants in Springfield were killing and eating household pets, he not only highlighted once again his own vulnerability to conspiracy theories, it put the immigrant community in Springfield in serious danger. Bomb threats have forced two consecutive days of school closings and some Haitian immigrants are now “scared for their lives.”

That’s dreadful. It’s inexcusable. But it’s not Trump’s only terrible moment in the debate.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Most notably, he refused to say — in the face of repeated questions — that he wanted Ukraine to win its war with Russia. Trump emphasized ending the war over winning the war, a position that can seem reasonable, right until you realise that attempting to force peace at this stage of the conflict would almost certainly cement a Russian triumph. Russia would hold an immense amount of Ukrainian territory and Vladimir Putin would rightly believe he bested both Ukraine and the United States. He would have rolled the “iron dice” of war and he would have won.

There is no scenario in which a Russian triumph is in America’s best interest. A Russian victory would not only expand Russia’s sphere of influence, it would represent a human rights catastrophe (Russia has engaged in war crimes against Ukraine’s civilian population since the beginning of the war) and threaten the extinction of Ukrainian national identity. It would reset the global balance of power.

In addition, a Russian victory would make World War III more, not less, likely. It would teach Putin that aggression pays, that the West’s will is weak and that military conquest is preferable to diplomatic engagement. China would learn a similar lesson as it peers across the strait at Taiwan.

If Putin is stopped now — while Ukraine and the West are imposing immense costs in Russian men and materiel — it will send the opposite message, making it far more likely that the invasion of Ukraine is Putin’s last war, not merely his latest.

But that’s not how Trump thinks about Ukraine. He exhibits deep bitterness toward the country, and it was that bitterness that helped expose how dangerous he was well before the Big Lie and Jan. 6.

Recall Trump’s first impeachment and the “perfect” phone call between Trump and Ukraine’s president, Volodymyr Zelenskyy. Ukraine had been locked in a low-intensity conflict with Russia since Russia’s 2014 invasion of Crimea and intervention in the Donbas, a region in eastern Ukraine, and Ukraine was in grave need of American military assistance. In his July 25, 2019, conversation with Trump, Zelenskyy said Ukraine was “almost ready to buy more Javelins from the United States for defense purposes.”

Trump responded almost like a mob boss. He needed a little something in return. “I would like you to do us a favor,” he said, “though because our country has been through a lot and Ukraine knows a lot about it. I would like you to find out what happened with this whole situation with Ukraine, they say CrowdStrike … I guess you have one of your wealthy people … The server, they say Ukraine has it.”

Recognizing that Joe Biden might be a formidable opponent in 2020, Trump also asked Zelenskyy to investigate the Biden family. This attempt to convince a foreign government to investigate a domestic political rival garnered the most attention and outrage about the exchange, but I want to focus on Trump’s first request, for Zelenskyy to find “the server.”

In that moment, Trump vocalized one of MAGA’s strangest conspiracy theories: that it was Ukraine, not Russia, that interfered in the 2016 presidential election, and that part of the proof was located in a mythical CrowdStrike server in Ukraine.

As Washington Post fact-checker Glenn Kessler explained in a 2019 analysis, “Trump has been obsessed with the idea that the FBI never took physical possession of the servers at the DNC that were hacked.” CrowdStrike is an American company that assisted in the investigation of the 2016 Democratic National Committee hack and leak. Trump believed that Ukraine had hacked the DNC servers and that somehow a DNC server was located in Ukraine.

Thomas Bossert, Trump’s first homeland security adviser, told ABC’s George Stephanopoulos in September 2019 that the theory was “completely debunked.” Yet Trump kept repeating it, leading Kessler to write later in 2019 that there were “not enough Pinocchios for Trump’s CrowdStrike obsession.”

As Kessler wrote, “It is dismaying that despite all of the evidence assembled by his top aides, Trump keeps repeating debunked theories and inaccurate claims that he first raised more than two years ago.”

“Dismaying” is a charitable word. When you think carefully about what happened here, especially in light of Trump’s relentless embrace of conspiracy theories both before and since, it’s deeply alarming.

At a critical moment in world history — when an American ally was seeking arms to help defend itself against a hostile great power — Trump responded with a corrupt and lunatic request: that Zelenskyy grant Trump a series of personal demands, including a demand that Zelenskyy couldn’t possibly meet, to find a server in Ukraine that did not exist.

Trump was conducting American foreign policy on the basis of his personal grievances, not American interests. Even worse, his negative attitude toward Ukraine isn’t rooted in a grand strategic vision; it is rooted in his personal pique over Ukraine’s nonexistent participation in a fictional conspiracy. It was an astonishing display of corruption and unfitness.

Trump’s defenders note that he did not get his way. The administration ultimately approved the Javelin missiles and Zelenskyy never had to investigate the Bidens, nor did he have to go on a server hunt. But that hardly vindicates Trump’s initial demand, and it’s cold comfort when contemplating a second Trump term.

Trump began his presidency by staffing it with a number of serious and sober-minded people in key positions. For example, Gen. Jim Mattis was the secretary of defense, Gen. John Kelly was secretary of homeland security, and Lt. Gen. H.R. McMaster was Trump’s national security adviser.

Time and again, they threw their bodies in front of potentially disastrous policy decisions. Mattis and Kelly reportedly even agreed “to schedule their travel arrangements so at least one of them could be physically accessible to the new president at all times.”

The effort to restrain Trump’s worst impulses placed responsible people under immense strain. McMaster resigned in 2018 after experiencing a difficult relationship with Trump. Mattis resigned in December 2018 in protest of Trump’s precipitous withdrawal of American forces from Syria. Kelly became Trump’s chief of staff in July 2017, but then left the administration at the end of 2018.

By the time of the Zelenskyy phone call, John Bolton — a respected member of the Republican establishment — had replaced McMaster. He was out 17 months later.

If Trump wins a second term, does anyone believe that he will hire people who are equally responsible? His new White House is much more likely to be staffed by the likes of Kash Patel, a Trump sycophant who rose to prominence by doing anything Trump wants. When Trump won the first time, there was no true MAGA infrastructure. Now he wants to radically remake the federal civil service. He’ll surround himself with an army of yes-men and there will be no one to check his worst impulses.

Those Trump defenders who are honest enough to acknowledge that Trump is self-interested and erratic try to turn his liability into an asset. They claim that world leaders are thrown off-balance by Trump and that they’re more cautious as a result.

But there’s a difference between “crazy like a fox,” when there is a method to the apparent madness, and Trump’s instability. He’s deranged in the most predictable (and thus manipulable) ways. In last week’s debate, for example, Trump’s memorable rant about Haitians eating pets was triggered by obvious bait from Harris.

As my colleague Ezra Klein points out in his debate analysis, Harris redirected a tough question about immigration by talking about Trump’s crowd size. In real-time, Harris’ tactic was so clear that I thought that even Trump would see what was happening. He could have immediately won the exchange by calling out Harris’ misdirection as an attempt to change the subject and then hammering home his points about the border.

But no. He couldn’t help himself. She pricked his pride, and he is nothing without his pride.

When the stakes are highest — for the election, for the country or for the international order — Trump isn’t just thinking about himself, he’s thinking about himself in the most unstable of ways. He can’t perceive reality. After watching him up close for nine years, our adversaries and allies know this to be true. They know he is both gullible and impulsive.

Trump’s reluctance to say the plain truth — that a Ukrainian victory is in America’s national interest — demonstrates that he is still a prisoner to his own grievances, and there is no one left who can stop him from doing his worst.

This article originally appeared in The New York Times.

© 2024 The New York Times Company

Originally published on The New York Times