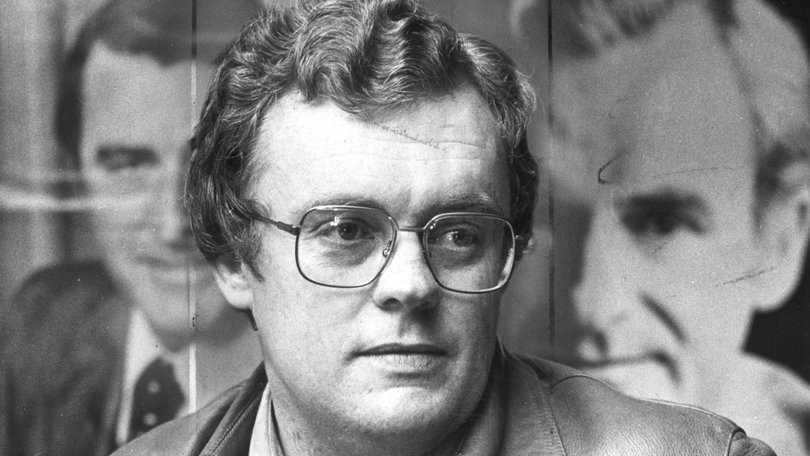

Graham Richardson: Labor powerbroker ‘Richo’ remembered as politically intelligent, sharp fixer

Graham Richardson, a key figure of Labor’s most successful federal government, was widely revered as a number-cruncher, fixer and kingmaker.

Graham “Richo” Richardson was a key member of Labor’s most successful federal government and the personification of much that was ugly in Labor politics.

As boss of the NSW Right and “Minister for Kneecaps”, he was widely feared as a number-cruncher, fixer and kingmaker.

Both during and after his time in politics, he was dogged by claims of sleaze and sharp practice.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Richardson denied almost everything but had only himself to blame if he wasn’t believed. After all, he called his memoir Whatever It Takes and in it, said he lied when he had to.

He was a major contributor to the factional stability enjoyed for most of the nine years of Bob Hawke’s government - before he threw his formidable influence behind Paul Keating - and the prime minister valued his acute political intelligence.

He also became a convert to the green cause and, as environment minister, fought successfully to save forests and stop polluting developments.

Later in life, he dealt with terrible illness with great courage.

Graham Frederick Richardson, who died on Saturday aged 76, was born in Sydney on September 27, 1949.

With father Fred, state secretary of the Postal Workers’ Union, and mother Peggy, his secretary, their only child was brought up in a highly political home.

By the age of 16, he reckoned he knew more about strength and weakness, betrayal and courage, and above all, persuasion than most politicians learn in a lifetime. He’d also adopted what passed for his political philosophy: winning is all that matters.

As a teenager, Richardson survived a near-fatal road crash, joined the Australian Labor Party and frittered away time at Sydney University.

He was soon rubbing shoulders with the young Turks of the NSW Right, such as Keating. More importantly, he came to the notice of the powerful state ALP president John Ducker.

At the age of 22, he became a party organiser and clocked up 80,000km around the state in the run-up to the 1972 election.

One of his jobs was to chauffeur ACTU president Bob Hawke. Richardson was thrilled by his charisma and aura of power and warmed to him because he didn’t treat his driver like rubbish.

As soon as Gough Whitlam’s victory was confirmed, he flew to London to chase girlfriend Cheryl Gardner. They married the following year and had a son and a daughter. Later, he had a son with second wife Amanda.

Richardson moved up to assistant state secretary in 1976. By then, Whitlam had been heavily defeated and the party was governing only in South Australia and Tasmania.

The surprise victory of Neville Wran in NSW that year was the start of the revival. Wran had become leader through a Ducker power play that Richardson watched with fascination.

Later that year, Ducker engineered the departure of state secretary Geoff Cahill and his replacement by Richardson. At 26, he was the youngest general secretary in NSW ALP history.

By the time Wran converted his narrow 1976 win to a landslide in 1978, Richardson was at the centre of power in the dominant faction.

In The Fixer: The untold story of Graham Richardson, Marian Wilkinson wrote that he soon realised corporate donations were far outstripping union money and became one of Labor’s greatest fundraisers in the big end of town.

According to Wilkinson, some of the money went into slush funds to entrench the power of the NSW Right in union elections and to solve messy problems such as paying off a candidate’s gambling debts.

As secretary, Richardson presided over a particularly murky period in NSW Labor politics. Labor identities were implicated in judicial inquiries into the drug trade following the murder of Griffith anti-drugs campaigner Donald Mackay and into the merchant bank Nugan Hand.

Just as damaging were the branch stackings organised by both right and left, which came to a head with the vicious bashing in 1980 of Peter Baldwin, a leading left activist and future federal minister who exposed gross stacking in the right-controlled Enmore branch.

The bashers were never caught. However, the chief suspect, Tom Domican, Joe Meissner and his girlfriend of later “Love Boat” infamy Virginia Perger, were charged, although ultimately acquitted, with conspiracy and forgery over the Enmore branch books.

Richardson had fought to get the charges dropped.

Ducker had quit as state party president by then and been replaced by Keating, who was thinking about the federal leadership held by Bill Hayden.

But Richardson was a Hawke enthusiast. He used the looming leadership battle to informally unite the disparate anti-left factions around the country against Hayden. His most important ally was the Victorian Robert Ray, whom he said was the hardest man he’d ever met in politics.

Richardson and Ray were to be the twin towers of the right during the Hawke government years.

One of the keys to Hayden finally stepping down for Hawke was his close supporter John Button telling him he should go quietly. Richardson helped persuade Button to intervene.

The 1983 election that brought Hawke to power brought Richardson to the Senate and soon he was one of the new prime minister’s main numbers men in caucus and an all-purpose fixer.

It was Richardson, from his toilet phone at the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, who defused a major party revolt by helping to talk Hawke out of allowing the Americans to test-fire MX missiles off the Australian coast.

Richardson joined the ministry, with environment and the arts, after the 1987 election.

The previous year, the podgy, gregarious lover of the urban good life had been shown Tasmania’s wilderness grandeur by future Greens leader Bob Brown.

“Having been shown the awesome forests and streams he wanted protected, I wanted to become a warrior for his cause,” Richardson later wrote.

Always the politician, he added: “That was a bad day for the logging industry in Australia, but a very good one for me, the environmental movement and the Labor Party. It didn’t take too long to work out that we had a perfect convergence: what was right was also popular.”

Richardson boosted the government’s green credentials.

He had the north Queensland rainforests given World Heritage listing but was roughed up by angry timber workers in the process - the only time he’d feared for his safety.

He had, despite the opposition of pro-development ministers, 378,000 hectares of Tasmanian forests protected and helped stop a Tasmanian pulp mill that threatened pollution.

His green preference strategy helped get Labor over the line in the desperately tight 1990 election.

Despite this, Hawke gave Richardson social security, a ministry he didn’t want, after clumsily offering, then withdrawing, defence.

Richardson was incandescent and from that moment, he became Keating’s man in the looming leadership battle - although ultimately the tribal loyalty of the NSW Right would have ensured that anyway.

He didn’t start serious plotting until late 1990 when, with Hawke slumping in the polls, Keating told him about the secret Kirribilli House deal.

Richardson tried to convince Hawke to leave voluntarily. When he refused, Richardson told the prime minister he knew about Kirribilli and a challenge was coming. He then briefed journalist Laurie Oakes about the deal - effectively the public announcement of the first and unsuccessful challenge.

In the period between the two challenges, Richardson played an odd role - massaging the numbers while publicly saying there’d be no second challenge - which led some commentators to believe he had a foot in both camps.

He had denied this, saying he was doing all he could do to help Keating without destroying the party. In the end, he even got Peter Baldwin’s vote.

“I am the only person in the world who had Richo’s kind services to help me become prime minister and to help me not be prime minister,” Hawke said.

Keating gave Richardson the job he wanted - transport and communications - but he did not have it for long.

Greg Symons, who was married to one of his cousins, was arrested in the Marshall Islands over an allegedly fraudulent business migration scheme. Richardson phoned the president, asking that Symons be allowed to return to Australia on bail.

When his intervention was revealed, the opposition and media had a field day. Although Richardson always maintained he did nothing improper, having cleared the phone call with foreign affairs and not purported to be acting on behalf of the government, he had to resign.

Richardson played a backroom role in the 1993 election and, after Keating’s unexpected victory, returned to cabinet as health minister.

He stayed only a year, and then quit politics, as he’d told Keating after the election that he would.

Richardson wanted to enjoy life and feared that, like his parents, he would die young.

After politics, Richardson became even closer to rich mates - especially the late Kerry Packer, for whom he worked for some years, and the late disgraced stockbroker Rene Rivkin.

Trouble followed him - including investigations into Sydney printing plant Offset Alpine, which burned down, resulting in an insurance payout more than three times its purchase price; and $1.4 million in a Swiss bank account that was allegedly Richardson’s share. He denied ever owning the shares. A three-year battle with the tax office was finally settled in 2008.

With these troubles behind him, he went back to political commentary, bringing a unique brand of avuncular cynicism, and backroom political manoeuvring.

In 2010, he played a part in the overthrow of yet another Labor leader, helping to unite the NSW and Victorian right wings behind the push that ousted Kevin Rudd and installed Julia Gillard as prime minister.

Richardson’s later years were dominated by his battle with chondrosarcoma, a rare form of cancer, and the increasingly radical surgery he had to undergo.

In 2015, he wrote, in intimate detail and with courage and good humour, about his affliction.

And a year later, while still in hospital after having his bowel, bladder, prostate and rectum removed, he resumed a newspaper column and television commentary.

About the same time, he backed John Coates in the bitter battle for the Australian Olympic Committee presidency. He owed Coates for being made mayor of the Sydney Olympic Village in 2000.

Richardson also resumed work on another book - not to be published until after his and others’ deaths.

The man who knew where the bodies were buried may yet, from the grave, rattle more skeletons.