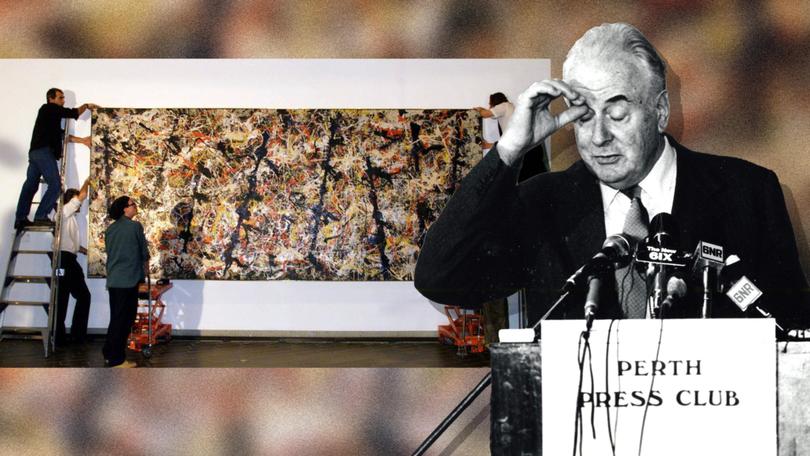

Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles and Whitlam: The untold story of an Australian political scandal emerges

The widow of acclaimed artist Clifton Pugh has claimed credit for helping convince Gough Whitlam to buy the Jackson Pollock painting, a purchase that had huge ramifications.

In 1973 a Judith Pugh got a phone call at her home in Victoria. Prime Minister Gough Whitlam was on the line seeking advice from her husband, artist Clifton Pugh, about whether the Labor government should approve one of the most expensive purchases of art in the world, Jackson Pollock’s Blue Poles.

Her husband was out. Mobile phones did not exist. Judith Pugh had been immersed in the art world her whole life, and gave Whitlam her enthusiastic endorsement.

When the expressionist painter returned, he was aghast at the advice. He correctly foresaw the $2 million purchase - about $14 million today - would trigger accusations of cultural elitism and financial profligacy at the Labor Party leader, who was forced out of office two years later.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Unfortunately for author Tom McIlroy, Ms Pugh chose to keep the anecdote to herself until this week, when she attended the Sydney launch of his account of the painting’s purchase, Blue Poles, Jackson Pollock, Gough Whitlam and the painting that changed a nation.

Brilliance and failure

Understanding the modern Labor Party is impossible without a sense of Whitlam. And no decision may better epitomise the brilliance and failure of his government than Blue Poles.

An abstract expressionist, Pollock was a leader of art movement that emerged after World War II which did not believe in life-like images. He painted by splashing household paint onto cavases lying on the floor, sometimes, while dancing. Mostly while drunk.

In 1973, the director of the under-construction National Gallery of Australia, James Mollison, decided he wanted to buy a painting regarded as one of Pollock’s six best works. The size of a living-room wall, the painting was a forest of red, yellow, blue, white and silver, although no one has ever really explained what it is.

“Titled at different angles and heights, the thick blue lines each featured small arms and offshoots,” writes Mr McIlroy, who studied art history at Melbourne University and is now a political journalist. “No two were the same. The unusual forms somehow succeeded in orienting the painting for Pollock and the viewer.”

Breaking the news

The agreement to buy the painting from a rich New York businessman (Pollock had long died, increasing the value of his works) was broken by journalist Terry Ingram for the Australian Financial Review in August, 1973. Mr McIlroy describes the article as the “scoop of the century”, a generous compliment to Mr Ingram, who died last year after declining to disclose his source, except to say they were “totally unconnected with the affair”.

A colleague suggested to Mr McIlroy the source may have worked for the Reserve Bank of Australia, which had to approve large cash transfers then.

The scoop was initially ignored by other media outlets. After a month, though, it became a big international and domestic story. Australian tabloids ridiculed Whitlam for buying a painting the comedian Paul Hogan would describe as looking like “a mess ... in a paint shed”. American newspapers, including the Washington Post, lamented how a weak US dollar had given foreigners the purchasing power to plunder important art.

Whitlam, typically, was unapologetic. His 1973 official Christmas card featured a photo of the painting.

In a speech to the Sydney Institute on Wednesday, Mr McIlroy acknowledged he is a grandson of the late BA Santamaria, a Catholic activist instrumental in keeping the Labor Party out of power from 1955 until 1972. There is evidence Santamaria encouraged Liberal leader Malcolm Fraser to seek Whitlam’s removal from office by the governor-general, an act the Labor Party still regards as its greatest betrayal.

Santamaria’s views on Blue Poles aren’t recorded in the book. A conservative, he was a trenchant opponent of Whitlam’s progressive social policies, which included greater public spending on the arts, an approach accepted by both sides of politics today.

But it is hard not to think he would have been proud of his grandson for making a thoughtful and interesting contribution to Australians’ understanding of their artistic and political history.