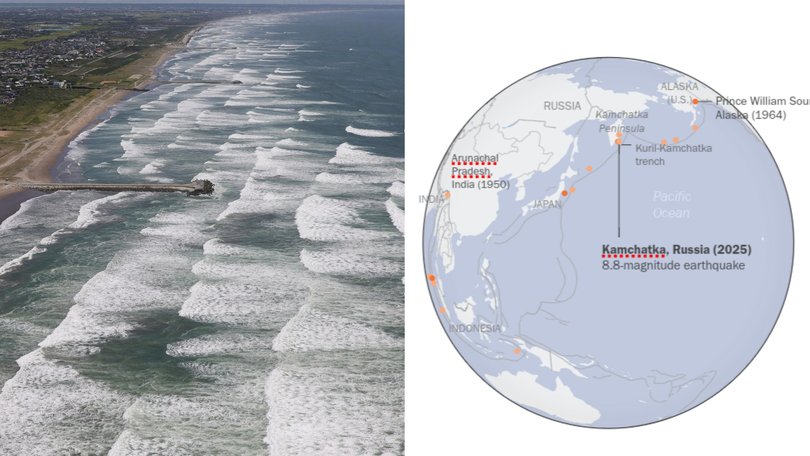

Why the 8.8 Kamchatka earthquake didn’t trigger a massive tsunami across the Pacific

An 8.8-magnitude earthquake off Russia’s coast sparked tsunami alerts from Japan to Hawaii — so why didn’t a devastating wave follow? Experts explain.

An 8.8-magnitude earthquake - one of the most powerful ever recorded - struck off the coast of eastern Russia late Tuesday, causing intense shaking for minutes, rattling windows and damaging infrastructure nearby.

In the following hours, people in Japan, Hawaii and along the US West Coast braced for an often deadly effect of coastal earthquakes: a tsunami.

Past strong earthquakes have caused massive and damaging waves far away, but scientists say these tsunami waves were tame by comparison across the Pacific basin, at least so far.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.Some areas of South America are still preparing for an incoming tsunami.

Researchers and response teams are still uncovering specific details about the event, but better warning systems and the other properties of the quake beyond its strength may have mitigated the effects so far.

“It definitely created a Pacific-wide tsunami, which in the context of tsunamis is quite large,” said Tina Dura, a tsunami researcher at Virginia Tech.

“But it’s a little bit smaller than could be possible in that magnitude of earthquake.”

The quake occurred near the Kamchatka Peninsula, where the Pacific tectonic plate is sliding underneath the North American plate. This seismically active “subduction” zone has produced two of the world’s top 10 earthquakes.

In 1952, a 9.0-magnitude earthquake hit less than 20 miles (32 kilometres) from the epicentre of Tuesday’s quake; that temblor also triggered a Pacific-wide tsunami.

The two plates slipped past each other at the relatively shallow depth of 12.5 miles under the ocean, which caused part of the seafloor to thrust upward and displace the water - creating a tsunami.

Wave heights reached much higher than normal near the Kamchatka Peninsula - more than 15 feet (4.5 meters) high, said Alexander Rabinovich, a physical oceanographer and vice-chair of the IUGG International Tsunami Commission.

He said local teams will be surveying damage to the low-population area along the southern coast of Kamchatka, where he said wave heights could have reached 50 feet.

In Japan, tsunami waves reached from 1 to 3 feet, according to the Japan Meteorological Agency. Around Hawaii, wave heights hit 5 to 6 feet.

Most places around California saw just a foot or so in increased wave height - though Crescent City, where tsunamis often get amplified because of the shape of its shelf, saw wave heights of almost 4 feet.

Why wave heights were relatively low farther from the quake “is the biggest question at the moment,” said Viacheslav Gusiakov, a tsunami expert in the Siberian branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences.

As the wave spreads out, it weakens.

But the similarly powerful 1952 earthquake in the same region caused bigger waves and more damage in Hawaii than Tuesday’s quake so far.

One possible explanation, Mr Gusiakov said, is a potential absence of a large landslide in the ocean that could have exacerbated the tsunami. Underwater movements of sediments or rocks can add to the energy of a tsunami by up to 90 per cent, although this specific case will need to be studied more.

It’s also possible that the earthquake itself, although powerful, may have contributed to a milder tsunami.

US Geological Survey modelling suggests the land shifted by 20 to 30 feet along a roughly 300-mile stretch of fault, said Diego Melgar, director of the Cascadia Region Earthquake Science Centre at the University of Oregon.

These sorts of variations in fault movement can be the difference between relatively small tsunamis and disastrous ones, he said.

For instance, the 2011 earthquake that triggered a nuclear crisis in Japan shifted the land by as much as 150 feet across a similarly long stretch of fault line, creating tsunami waves that were as high as 100 feet locally.

It also caused millions of dollars in damage in Crescent City, near the Oregon border, and swept one person away.

“Earthquakes have a personality,” Mr Melgar said.

“Those kinds of details really affect the tsunami.”

Part of the answer is also better warnings, experts said. Tsunami warnings were issued in a timely manner by the Kamchatka and Sakhalin tsunami warning centres, Mr Gusiakov said.

So far, no tsunami fatalities have been reported.

The surge of water did cause a deck to break off in Crescent City, but no injuries have been reported so far. Mr Rabinovich said the tsunami warnings were quite effective this time around, allowing people time to evacuate from coastal areas, take boats out of harbours and prepare.

“When you’re all the way across the Pacific Ocean, you do have a little bit more time to get everyone aware and prepared,” Ms Dura said.

That’s not always the case. For example, she said an event could unfold in minutes to hours in the western United States from a rupture in the Cascadia subduction zone.

It’s too early to say that the earthquake did not cause any disastrous tsunami damage, Mr Melgar said.

People have become used to seeing disaster impacts broadcast live on social media, but it will take careful analysis of satellite data as well as boots-on-the-ground surveys to know the height of waves that hit the Russian coast, particularly in the sparsely populated Kamchatka Peninsula.

Even though any tsunami impacts were minimal in Hawaii and on the US West Coast, Mr Melgar called it “a story of triumph” that those areas received warnings and acted quickly.

Some warning systems have been implemented in response to deadlier and more damaging earthquakes. The 1952 earthquake near the Kamchatka Peninsula caused significant damage in Hawaii.

In 1946, an 8.6-magnitude quake in Alaska’s Aleutian Islands triggered a tsunami that killed 159 people in Hawaii. Those disasters were the driving force behind the creation of the US Tsunami Warning Centres, which are part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

“Any warning at all is a huge success,” Mr Melgar said.

© 2025 , The Washington Post