THE ECONOMIST: Beware the scorching gold price rally driven by speculators

THE ECONOMIST: Only one explanation for the surge makes sense and it will not reassure investors.

The jargon of gold trading echoes that of poker. “Strong hands” are investors loyal to the metal, no matter the price. “Weak hands” are flaky punters who fold at the first sign of trouble.

Bullish investors win when they convince others of their story for why the price is rising, which boils down to why, this time, strong hands outnumber weak ones. Their bluff is called when the market softens. If the price does not rebound, their story collapses. If it does, it gains credence.

This year, the bulls are winning so comfortably that the argument would seem to be over. After the gold price hit $US4380 ($A6704) an ounce, a record, on October 20, it fell by more than 10 per cent — only to recover some of its losses.

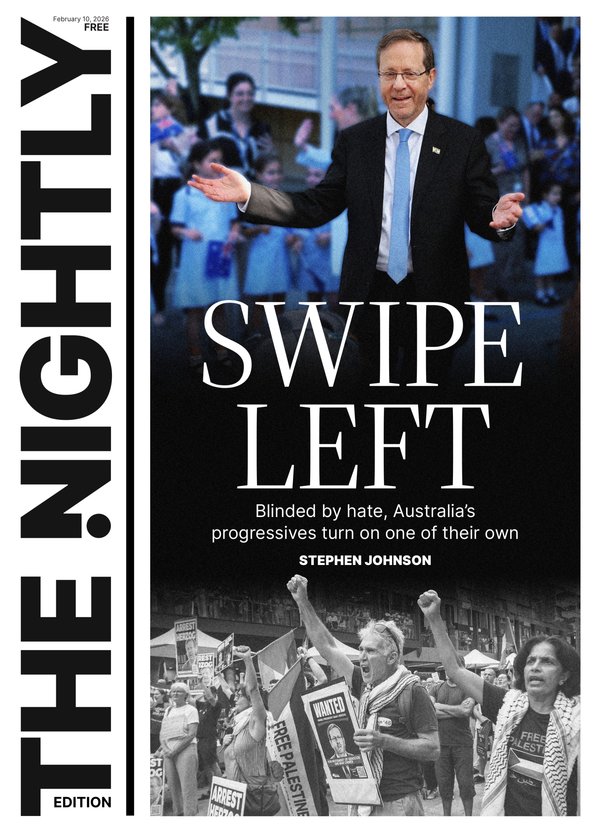

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.It is now 55 per cent higher than in January and 47 per cent past its previous inflation-adjusted peak, reached in 1980. Many analysts predict it will break $US5000 by the end of 2026. Then again, early this year, none had anticipated it would cross $US4000 in 2025.

Do theories explaining its soaring price make sense?

Each rests on a different buyer: institutional investors, central banks and speculators. Begin with the institutions. Gold’s main attraction is as a store of value, especially in times of crises. It is tangible, easy to transport and comes in standard-sized bars tradable on a global market, which reassures investors with big portfolios.

Gold’s previous bull runs occurred after the dotcom crash and the global financial crisis of 2007-09, and during the COVID-19 pandemic.

This time, however, a different dynamic is at play. The gold price has roughly doubled since March 2024, despite the lack of a recession. America’s S&P 500 index has risen by more than 30 per cent over the period; real interest rates remain high.

Perhaps institutional investors are seeking refuge in gold since they fear a crisis is near. This year, President Donald Trump’s tariffs and his standoff with China have threatened trade chaos. Wars in Europe and the Middle East might have spiralled out of control. America has experienced its longest-ever government shutdown.

Fears are mounting that an AI-stock crash could bring down the real economy. But it is tricky to reconcile these on-again, off-again shocks with the almost linear climb of the gold price. The metal was already hot early this year, when warnings of an AI bubble were less audible.

Mr Trump’s trade deals, his truce with China, peace in the Middle East — none have had much impact on its price. After America’s shutdown came to an end on November 12, stock markets rose, then slumped, but that was because the odds of an interest-rate cut by the Federal Reserve fell as well. Gold’s rebound accelerated.

A second explanation contends that the gold rush is being driven by central banks — seeking protection not against short-term meltdowns but longer-run changes.

According to this “debasement” theory, America’s political dysfunction and ballooning public debt, as well as threats to the independence of the Fed, are feeding fears of rampant inflation and killing faith in the greenback, causing central banks worldwide to swap long-duration, dollar assets for safe-as-houses gold.

The problem with this story is that it lacks evidence.

Were American securities being dumped en masse, the dollar would be falling, and long-term yields would be rising. In reality, the dollar has been pretty stable after slumping earlier this year; yields on 30-year Treasuries have been mostly flat.

Proponents of debasement point out that emerging-market central banks are keen on the metal. If gold’s share in central-bank reserves is up, however, that is largely because its price is rising while the dollar is not. In volume terms, emerging-market purchases of gold, which started from a tiny base, remain small.

A confidant of central-bank officials detects no urge to bet the farm on gold, especially if doing so would mean chasing a bubble: “Most are going to hold the position for many years. They would fear having to book losses for ever.” IMF data suggest that their reported buying has slowed, not accelerated, since last year, and purchases are driven by just a handful of banks.

This leaves speculators as the most likely drivers of recent price movements. On September 23 — the last time America’s Commodity Futures Trading Commission released data, owing to the shutdown — “long” positions held by hedge funds on gold futures were at a record 200,000 contracts, equivalent to 619 tonnes of metal.

Net purchasing by exchange-traded funds was also strong. Last month ETF flows ebbed; that, together with just 100 tonnes’ worth of net sales by hedge funds, would explain much of the price dip observed late that month, estimates Michael Haigh of Société Générale, a bank.

ETF flows have since rebounded (hedge-fund data remains unavailable). It would, therefore, appear that the gold price closely tracks these flighty funds’ appetite.

What may have started, months ago, as a limited push for more gold in central banks’ reserves thus seems to have snowballed into a self-propelled mass of hot money chasing prices higher. That is a bad omen for “strong hands”.

At some point, this classic “momentum trade” — of investors following trends — will stop. The longer it lasts, the more chips the brashest players stand to lose at the end.

Originally published as Beware the scorching gold rally