THE ECONOMIST: Feuds, grudges and revenge — Welcome to the dark side of the workplace

THE ECONOMIST: Companies pay a heavy price to pay for conflict culture in the workplace.

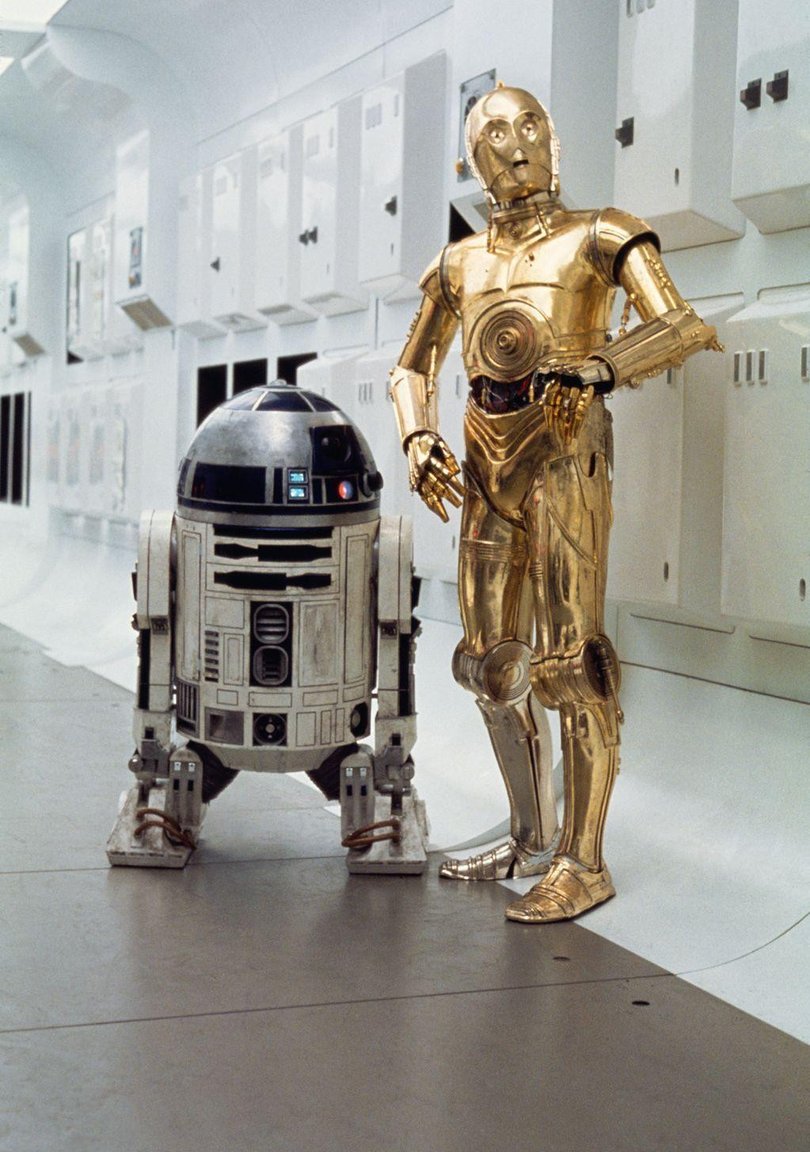

One of the more touching on-screen relationships is that between C-3PO and R2-D2, two robots who appear in the “Star Wars” films. The actors behind the droids got on less well.

“He was in a box he couldn’t do anything with,” Anthony Daniels dismissively said of Kenny Baker, the man who played the part of R2-D2. “Rude to everyone”, was Baker’s verdict on his fellow actor.

Antipathy need not prevent good work. Messrs Baker and Daniels managed to put aside their differences on set (it must help to be able to roll your eyes without being seen).

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.And friction can be good for organisations: a contest of ideas about how to get something done ought to yield better outcomes. But such “task-related” disagreements can easily curdle into something more personal and destructive.

Every workplace has a simmering feud or long-running grudge.

These fractured relationships can exact a heavy price. Research published for Acas, a mediation service, in 2021 put the annual cost to British organisations of resolving work conflicts at £28.5 billion ($59b), factoring in resignations, sick leave, dispute resolution and the like.

And that’s before you take into account the hidden costs of withheld co-operation and time lost on Gothic revenge fantasies.

Humans are hard-wired for disagreements to escalate. One of Lindy Greer’s favourite classroom exercises at the University of Michigan’s Ross School of Business is to have students at different tables learn slightly different rules for the same game (aces high in some cases, aces low in others, for example).

When people move tables and start to unexpectedly claim victory, other players are far quicker to assume they are stupid or cheats than to question whether they have a different understanding of the game.

This is a good demonstration of the “fundamental attribution error” — the tendency for people to assume that the actions of others are determined by their personalities, not by external factors.

Once someone feels they have been intentionally wronged, their instinct is to get even. “The Science of Revenge”, a recently published book by James Kimmel, argues that a desire for vengeance activates the same brain circuitry as a drug addict thinking about their next hit.

In a study conducted by David Chester of Virginia Commonwealth University and C. Nathan DeWall of the University of Kentucky, participants played a computer game in which a virtual ball is tossed between three players; in some iterations of the game, the ball is passed back and forth between two of them, conspicuously ignoring the third player.

Rejected players are shown a visualisation of a voodoo doll representing their partners, and asked to choose how many pins they would like to stab it with. The moral of the story: pass the ball to everyone.

Organisations have features that are particularly liable to stir up bad blood. Power struggles pervade firms: Ms Greer’s research suggests that people on senior leadership teams can be particularly sensitive about protecting their turf. Organisations can also make forgiveness harder, says Thomas Tripp of Washington State University.

Dispute-resolution processes are definitely better than people seeking to exact their own revenge (“a very sloppy form of justice”, he says) but overly legalistic approaches can also serve to drag things out.

The solution to all this seething lies partly with managers. Disrespectful corporate cultures are fertile ground for feuds. It’s usually worth bosses trying to sort out ructions informally before getting HR involved. Framing some types of disagreement as being for the good of the firm might stop conflict escalating.

But individuals are best placed to stop things from spiralling out of control. Ms Greer recommends asking follow-up questions whenever you are in a disagreement, so that you understand where someone is coming from rather than assuming the worst of them. And if you ever end up ruminating about an apparent slight, Mr Tripp recommends the adage known as Hanlon’s razor.

“Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity,” is not the most generous way to interpret the behaviour of colleagues. But it might help subdue your craving for revenge.

Originally published as Feuds, grudges and revenge