From novice to protege, how Indigenous artist Alfred Lowe channels Australia’s beauty one sculpture at a time

Alfred Lowe did not set out to become a world recognised sculptor — despite being surrounded by art during his childhood in Alice Springs

Growing up in Alice Springs, Alfred Lowe was surrounded by art.

His father was a musician, his mother a painter and he lived right next to the Araluen Art Centre and spent his childhood weaving in and out of the gallery.

But his first career path was something radically different — community health — a field he worked in until the pandemic when he reached the point of burnout.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.“I needed a break,” he said in an interview over Zoom.

He took leave and returned to studies and on afternoons would meet his mate Zaachariaha Fielding who was working out of the APY Collective’s Adelaide Studio.

This is where Lowe, aged 25, first met clay.

“I just started doing ceramics, it happened quite quickly,” he said.

“I just started hand building, I did a small hand-building class and made my way into it, that was three years ago now.”

Mr Lowe said with clay he felt an instant connection that he hadn’t experienced with other mediums.

“With painting and drawing and 2D mediums, I would get stuck just staring at this blank space not knowing what to do,” he said.

“Ceramics forces you to pay attention and be in the moment and not overthink things.

“You don’t really get a chance to be constantly second-guessing yourself, once it’s done, it’s done.”

The three forms of ceramics include wheel-thrown pottery, slip casting where clay is poured into moulds and handbuilding, which is Mr Lowe’s speciality.

“So you’re rolling the clay out into coils and stacking them and joining them up together,” he said.

“It’s more time on a simple piece, more time on one pot or sculpture or vessel.”

He describes his work as fine art.

He also tried his hand using forms sent to other artists at the APY Collective by Mud Australia, the upscale ceramics company founded 30 years ago by Shelley Simpson with boutiques in London, New York and Australia.

Mud is best known for its mugs, plates and bowls which are famed for their thin ceramic design, elegant simplicity and exquisite colour range and the brand is beloved by the English cook Nigella Lawson.

In its 30th year, it just opened its newest boutique in Islington, London and the glamorous television cook and cookbook author was among those who attended the launch.

Ms Simpson said she saw an instant genius as soon as she saw Alfred’s work which she described as fresh, extraordinary and really unique.

“It’s incredible that Alfred’s created this beautiful practice in three years,” she said.

“To find your thing in that short period of time means that it was always there to begin with.

“People have a connection with clay and they can’t stop.

“It’s almost like an addiction for those who really get it, they just have to do it.”

A supporter of the defeated Indigenous Voice to Parliament referendum, Ms Simpson wanted to contribute something to the debate after the “difficult year”.

Instead of opening her Shelley Simpson ceramic prize up like normal, she decided she would celebrate an up-and-coming Indigenous artist.

“I think a lot of white Australians have felt really hamstrung or kind of helpless in the last 12 months,” she said.

“There are no rules, it’s my ceramics prize, I can do with it what I want to do with it.

“And this for me was an amazing way to celebrate and celebrate work that I love.”

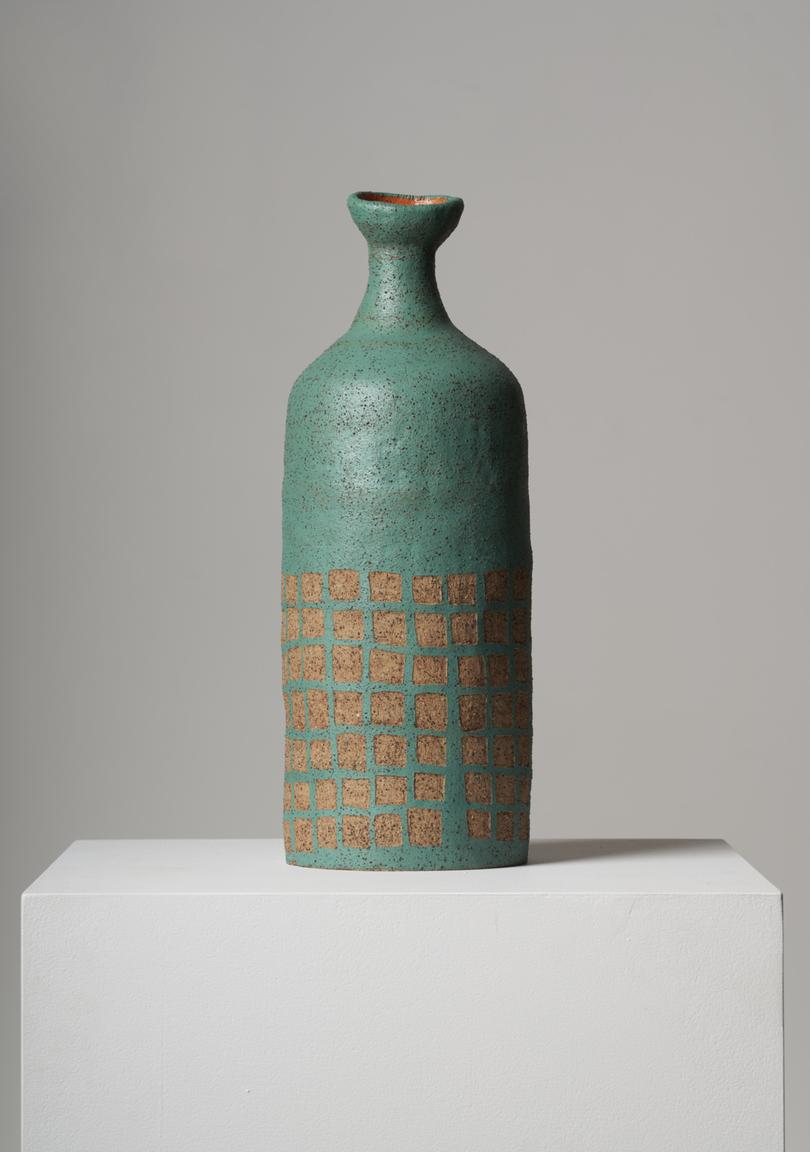

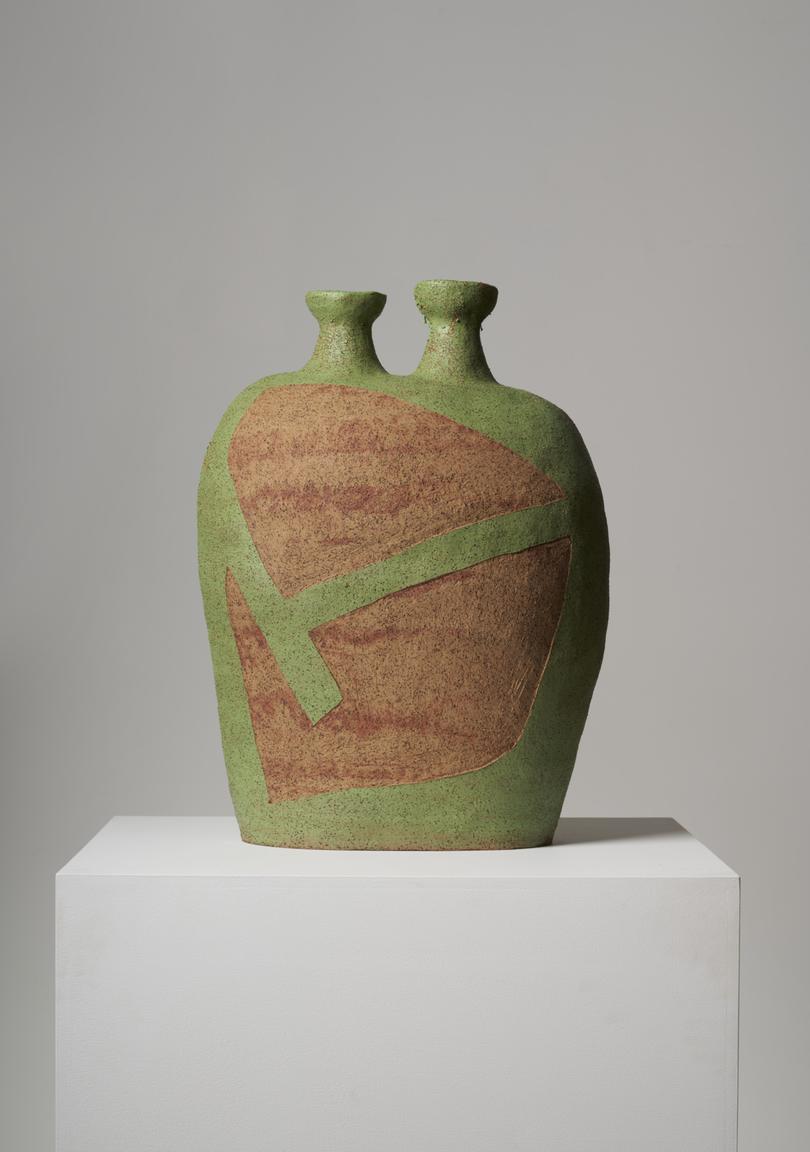

As part of her 2024 Shelley Simpson Ceramic Prize she is showcasing Alfred Lowe’s works in her boutiques including in New York and Central London where they sold out.

For his part, Mr Lowe said he wasn’t surprised by the referendum result, because Australians do not grow up learning much about contemporary indigenous culture.

“I expected it,” he said, without a tone of resignation rather than rancour in his voice.

“Part of the problem in Australia when it comes to First Nation’s people there’s just a serious lack of education,” he said.

“There’s nothing taught about what modern-day racism looks like and what modern-day systemic racism looks like.

“You don’t have to be racist to be enforcing systemic racism.”

He said Australia’s tall-poppy syndrome was a factor in the rejection of the Voice, because of the perception that Indigenous Australians might receive something more.

For now, he is focused on channelling his culture into his work.

“Being black — it’s informed everything in my life and it’s given me a unique story, a unique view of the world,” he said.

“This idea of living between two worlds, this Western world and First Nations other world specifically.

“Although I’m new to the medium of clay and new to my practice as an artist, I’m not new to the idea of storytelling and the practice of storytelling.

“What I’ve done in the last three years is just change how I tell the stories.”

He said his goal was to have his work noticed.

“These sculptures — you can love them or hate them but you can’t really ignore them,” he said.

But he said the imperfect beauty of his natural environment was also inspiration.

“Central Australia and particularly where I grew up is known for the MacDonnell ranges,” he said.

“And a lot of beauty that comes from mountains is actually from floors and from the parts of the mountain that have been eroded away or rusted.

“And so I want that to come across in the work — this beauty that’s created in the imperfect natural (environment.)”

He said he hoped to see an expansion of Indigenous art and culture in more mediums, including film, textiles and television.