THE ECONOMIST: The gilded glory days of glossy magazine editors like Devil Wears Prada inspo Anna Wintour

THE ECONOMIST: Once upon a time, magazines were how the ‘have-nots’ were given a glimpse into the rich world of the ‘have-yachts’

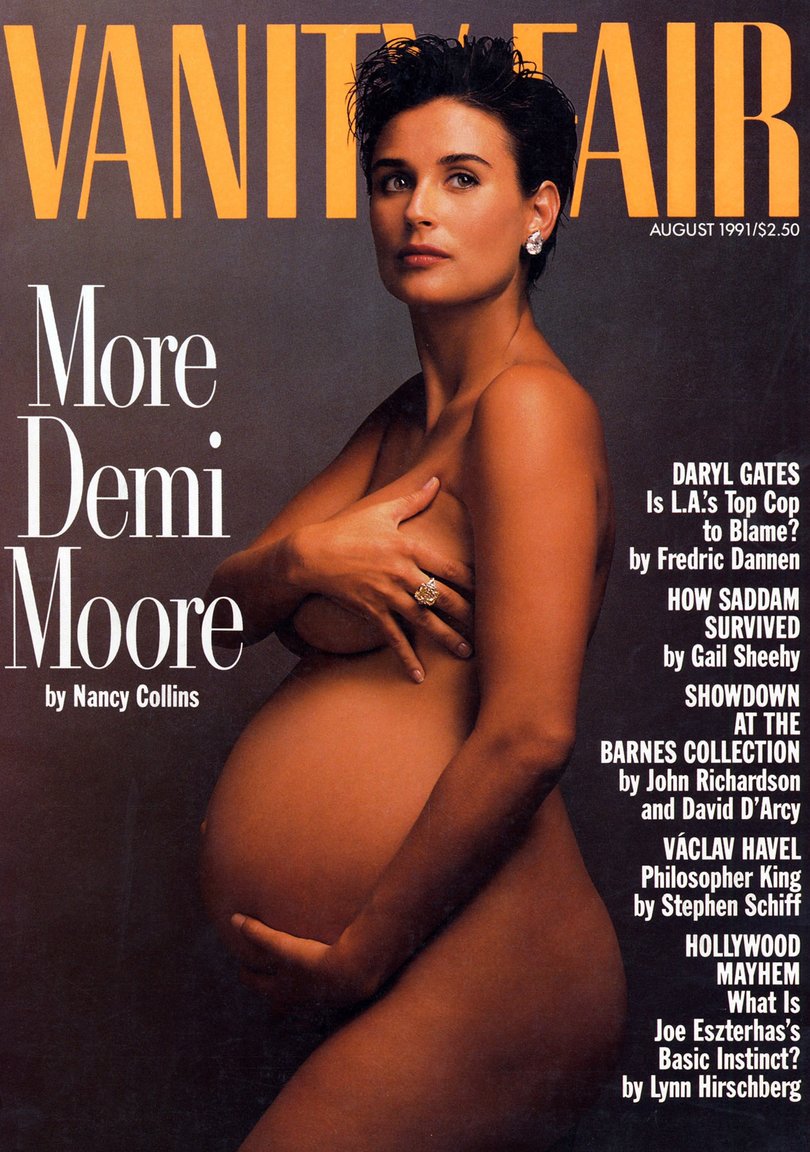

“Fucking” was forbidden. So too was “chortling”, “quipping”, “donning”, “penning”, “opining” and — lest that list of linguistic prohibitions left any writer feeling faint — “passing away”. The list of banned words in Vanity Fair was, for such a glamorous magazine, parsimonious, even pious: “glitzy” was vetoed; “hookers” were out; hair must not be “coiffed”; one never ate in an “eatery”. Condé Nast’s magazines may have celebrated fancy living, but they did so in plain English.

What these magazines said, and how they said it, mattered. It is hard to remember in this era of Instagram, when the many (influencers) tell their (relatively few) followers what to do, but once upon a time the few told the many.

To be precise, glossy magazines did the telling and, to be more precise again, Condé Nast did. The Instagram world in which “pretty people do pretty things in pretty places without you” is, as Michael Grynbaum makes clear in one of two new books about magazines, merely “a DIY replication” of the role that Condé Nast held in the 20th century.

Sign up to The Nightly's newsletters.

Get the first look at the digital newspaper, curated daily stories and breaking headlines delivered to your inbox.

By continuing you agree to our Terms and Privacy Policy.

For a handful of decades a handful of magazines like GQ, Vanity Fair and Vogue dictated to the whole world what was “hot” and what was not, who was “in” and who was “out”, and along the way offered readers lashings of “Sex”, “Cool!”, “Hollywood!”, “Rah!” (whatever that might be) and — of course — exclamation marks!

It all began rather more mutedly. Vogue was founded in 1892 to celebrate a Wildean world of manners before morals. During the Spanish-American war in 1898 the magazine warned readers not to dress in patriotic colours since “Bad taste never yet helped a good cause.”

By 1909 it had been bought by Condé Nast, a New York businessman, who wished it to aim at “class, not mass” — a phrase that to British eyes (and some ears) has neither rhyme nor reason since, as any Fleet Street hack could tell you, to succeed magazines need mass, not class. At times, Condé Nast had neither: outside the printworks were two obelisks engraved with the words “VOGVE” and “HOVSE & GARDEN”. This, some felt, was a trifle VVLGAR.

But who cared, when it was all such fun? For the best part of a century Condé Nast’s magazines were the best way for the have-nots to peer at what a new book nicely calls the “have-yachts”. They were a “two-way mirror” into the world of the rich, as Mr Grynbaum puts it.

This world was very rich indeed: an artwork by Jackson Pollock hangs in a bigwig’s house; supermodels hang around at parties; everyone hangs the expense. There were low patches: a mid-century slump in which Vogue went out of vogue; Vanity Fair fell into a slough of despond and the New Yorker insisted on running lengthy articles on the future of wheat. But under a new clutch of editors in the 1980s and 1990s — Dame Anna Wintour, Graydon Carter, Tina Brown — Condé Nast enabled the world to ogle the rich once again.

Gloss it up The subtitle of Mr Carter’s recent memoir calls this period, roughly from the early 1980s to the financial crisis, “the last golden age of magazines”. It is a grandiose title but one that feels fitting: in this more monkish era the excess here feels as unimaginable as that of imperial Rome. An expenses bill for a GQ feature on dining in Japan comes to $14,000 US (“Is that all?” asks an editor). When Mr Carter arrives at Vanity Fair he finds there is “no budget at all — that is to say, the budget had no ceiling”.

If the budgets were big, the names were bigger. It was an era before the internet had fractured publishing and the “splinternet” had fractured celebrity.

Writers such as Christopher Hitchens became household names; editors were internationally famous and, at times, infamous.

Filming has started on The Devil Wears Prada 2, inspired by a roman à clef about a villainous magazine editor by a former assistant to Dame Anna.

The editor, reportedly called “Nuclear Wintour” by her colleagues, has said it is “for the audience . . . to decide if there are any similarities” between her and the character.

Modern hacks should mourn the loss of the journalism: few magazines today can afford to commission earnest 10,000-word articles about things like grain. In truth most will mourn the loss of the drinks trolleys — not to mention the dinner ones which, at another paper, arrived at writers’ desks complete with wine and a uniformed flunkie. They may not, perhaps, envy the hangovers: one morning, Hitchens had to be retrieved from a golf course where, “still in the wrinkled off-white linen suit from the night before”, he was “heaving up”.

Condé Nast’s magazines were, at times, a little nasty. This was an era when people would “check your privilege” — chiefly to make sure you had some. If you applied for a job as an assistant at Vogue in the 1990s you would be handed an alphabetised, intimidating list of 178 items from A (Pedro Almodóvar) to W (Billy Wilder), via Manolo Blahnik, Mrs Dalloway and the phrase “For a long time I used to go to bed early.”

If you could correctly identify two film-makers, a shoemaker, a modernist masterpiece and the first line of Proust, then you could become part of the elite club Mr Grynbaum describes. Some of this was sensible: educated workers were needed since, as Ms Brown put it, these magazines had to “make the sexy serious and the serious sexy”. Some of it was pure gatekeeping: snobbery in spectacles.

But then these magazines sold: an issue of Vogue with Hillary Clinton as cover girl shifted 700,000 copies. The Going, as Mr Graydon’s title has it, Was Good. Perhaps this was due to the skill of him and his colleagues. But editors are often praised for their talent when in truth what they have is timing. Then, in the late 1980s, the computers came. One art director at Vogue declared them “a phase”.

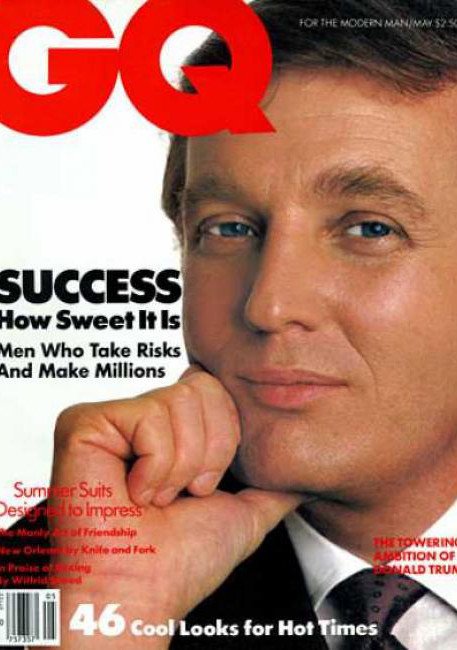

Today many of the top editors, including Dame Anna and Mr Carter, have retired or stepped back. These magazines are not quite history, yet their era of overweening influence is. Except, perhaps, in one odd way. In 1984 GQ featured a suited man beneath the headline “SUCCESS — How Sweet It Is”. That led to a book, then a TV series. The series was called The Apprentice; the book The Art of the Deal. The man would become president

Empire of the Elite by Michael Grynbaum, Hachette, paperback $34.99 out now, hardcover $49.95 from October 14.

When the Going Was Good. By Graydon Carter. Allen & Unwin, $45 out now.

Originally published as Booze, bills and $500,000 photoshoots: the golden age of magazines